In this episode, we enter the world of US Treasury operations with a focus on the recent resolution of the debt ceiling—often perceived as crisis averted. Yet, is everything truly back to normal? As the Treasury prepares to refill its TGA coffers, we're going to dissect the mechanics of this operation, the role of bank reserves, the Fed’s reverse repo window, and the underlying complexities that could impact financial markets.

Today’s Bullets:

The Treasury General Account

How much does the Treasury need?

Reserves and Reverse Repos

State of the Great Re-Funding

Join the 🧠Informationist community and get access to every post + the entire archive of articles.

You’ll soon understand the most important financial topics around you, easily and quickly. That’s my guarantee.

Relevant Charts:

TGA Depleted:

TGA Typical Level:

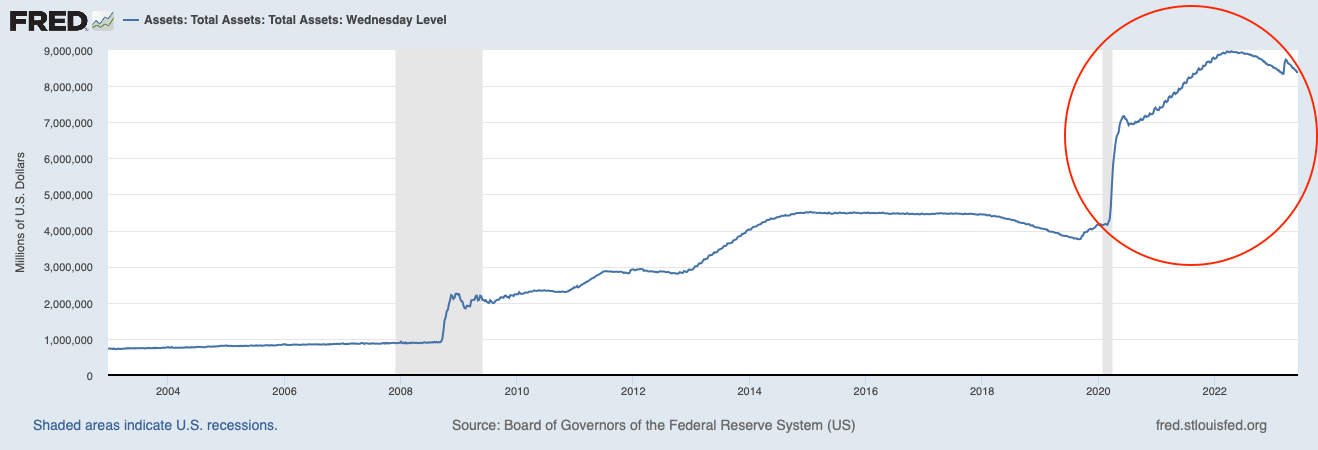

Fed Assets after 2020 QE:

Bank Reserves:

Reverse Repo:

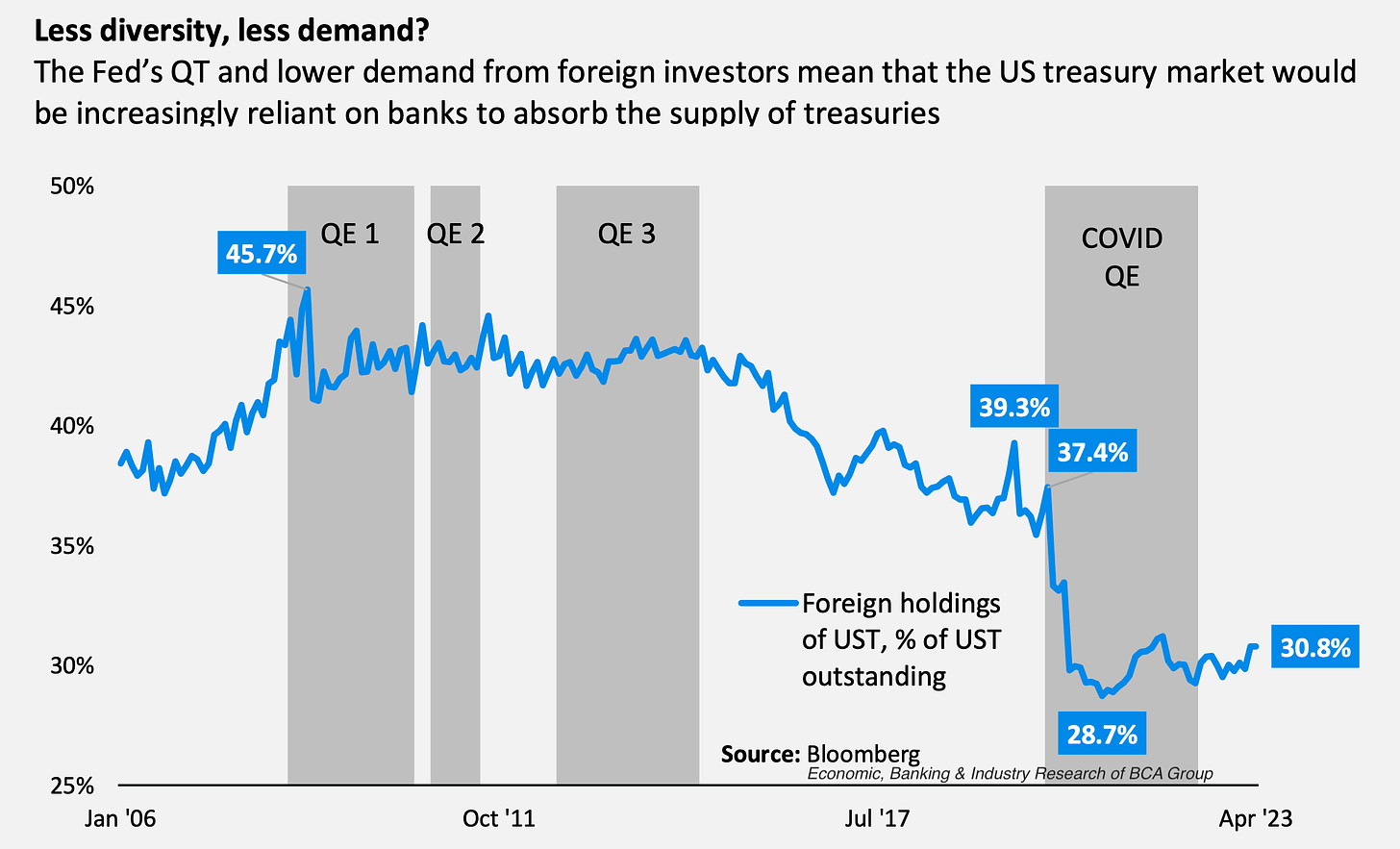

Foreign Demand for USTs Falling:

Links:

Full Transcript:

The debt ceiling issue is resolved, so the US Treasury can pay all its obligations to various programs and contractors again. And most importantly, it won’t default on US Treasury debt.

So then. Crisis averted. All is good right?

Right?

Well….maybe.

Because now that the Treasury has been approved for a larger line of credit, it has to fill the piggy bank back up again. Like a hoover vacuum, The Treasury is about to suck up market liquidity all around it. And by the estimates of Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan, to the tune of over $1 Trillion.

Oink, oink. 🐷

But where is all that cash going to come from? And what will be the impact to the markets when the vacuuming begins?

Excellent questions that many people have started to ask recently. Ones that could impact your portfolio and its performance, too. So, this is a super important topic — one I wrote about recently.

So let’s unpack all this nice and easy, as always, and then we’ll check in on the Treasury and see how they’ve been doing with all this hoovering so far..

First, what exactly is the Treasury General Account? Well, just like it sounds, this is basically the US Treasury’s checking account.

Where it holds cash and pays its bills.

If you’ve been watching the debt ceiling drama, you may have also noticed that the account balance has fallen to a precipitous level. Dangerously close to the point of being overdrawn.

Except unlike a checking account at a bank, there is no overdraft protection for the TGA. Once it hits zero, there’s no courtesy call and $30 convenience fee, it’s simply game over.

The Treasury defaults.

So, thank God for the heroics of Congress, the Senate, and the White House, all rushing to Janet Yellen’s distress signals from the last few months.

Except they waiting until the absolute last second before the Treasury became insolvent.

And now the Treasury is ready to turn the spigot back on and refill its coffers.

But how much liquidity do they need, and where will it all come from?

Some people assume it’ll come from bank reserves and the massive reverse repo balances banks have been sitting on.

But it’s a bit more complicated than that, so let’s investigate.

The first big question is how much debt does the Treasury need markets to soak up, and how fast do they have to do it?

Recent reports have suggested that the Treasury targets to return the TGA balance to approximately $550B by end of June.

This seems to fit with the recent balances and would make sense after the surge in M2 during 2020 (due to massive money printing).

Which means the Treasury needs to float about $500B of USTs over the course of just a few weeks. Not a small sum, but not quite crippling either.

A couple of nuances, though, as that may not be the full amount they need to raise.

First, there’re a total of about $225B of Treasures that maturing in June and need to be replaced—remember, the US operates in a perpetual deficit and must borrow more to pay off old debts.

This is why the TGA doesn’t just get replenished with US government ‘profits’ or tax revenues. They are all already spent, and then some.

Also, do you remember the whole “extraordinary measures” statement from Yellen a few months ago? You know, the one where she said the Treasury would skip out on payments to certain retirement programs and other government obligations in order to ensure The Treasury didn’t default on any debt?

Right. That means the Treasury has been robbing Peter to pay Paul, as they say.

And so, on top of refilling the TGA, and paying off maturing debt, the Treasury also has a few internal past-due tabs it needs to clear up, too.

And this is why Goldman and JP Morgan are estimating the total amount of capital the Treasury needs to raise is more along the lines of $1T to $1.1T.

And this is before any QT that the Fed has been trying to accomplish. You recall that this is selling the USTs that are on the Fed’s balance sheet after buying debt during 2020 with money created out of thin air by the Treasury.

The Fed has been trying to roll that off its balance sheet to help battle inflation, and the current target is to sell approximately $95B of total assets per month.

OK, then where is all this needed liquidity going to come from? Bank reserves? The reverse repo slush fund?

And how fast are we talking here?

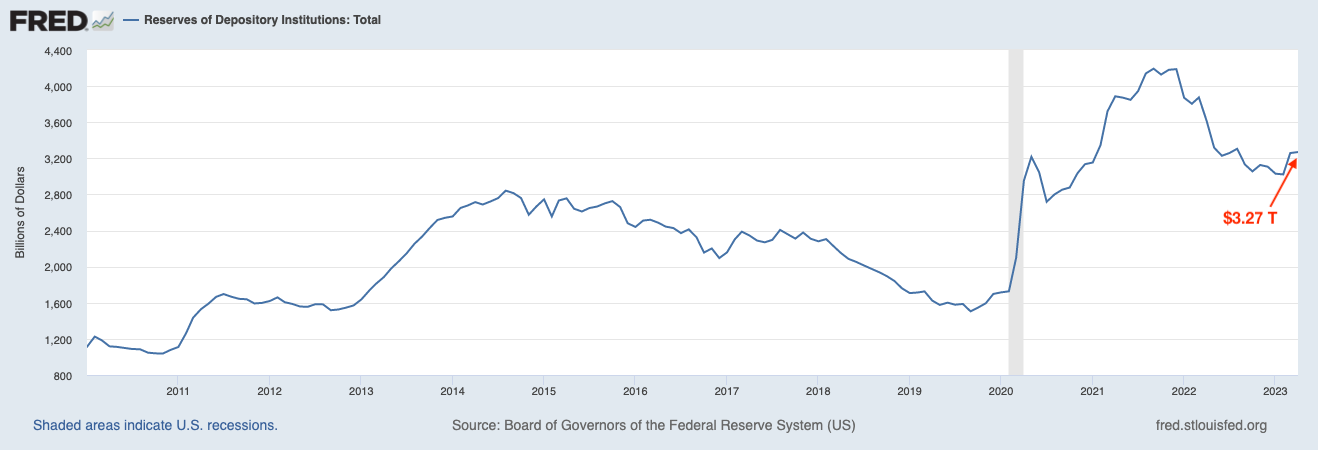

A little recap on banks and their reserves. These are essentially deposits that the banks keep on hand in order to meet leverage and liquidity requirements, as set by the Fed.

And even though the requirement was reduced to zero by the Fed during 2020, banks must meet the Fed and bank regulators’ required Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). Plus, banks have their own internal liquidity measures and requirements. After all, nobody wants to end up like Silicon Valley Bank or First Republic.

As of right now, there are a total of $3.27T of reserves in US banks.

So, if the Treasury needs $1 trillion, we’re talking about draining 1/3rd of those reserves. In a month.

This would be massive and effectively a form of additional QT.

Remember what we just said a few minutes ago. The current QT plan is about $95B per month. The $1T of US Treasury needs would amount to over 10X that amount.

OK, where else can the Treasury draw from?

The reverse repo slush pile, of course. Maybe.

I talked about all about repos, reverse repos and more in a recent newsletter. If you didn’t see that or want a refresher, you can find a link to it in the show notes.

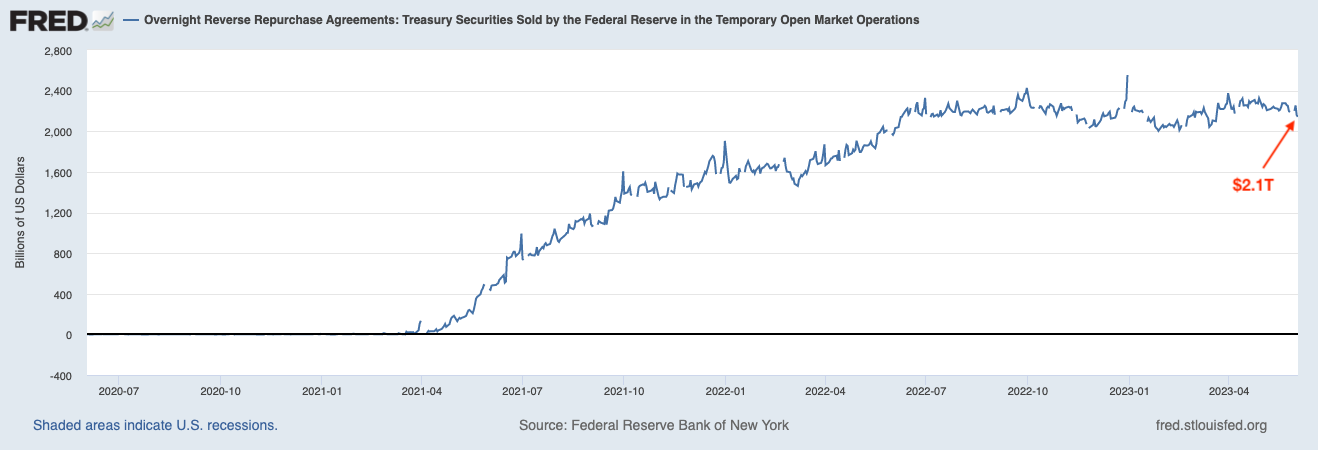

But basically, reverse repos are a way for banks to park excess cash at the Fed to earn interest in lieu of reserves. After the Great Money Printing of 2020, a number of banks found themselves sitting on massive piles of cash.

How much cash?

Would you believe $2.1T?

See, banks are limited in the amount of Treasuries they can buy due to the (SLR or Supplemental Leverage Ratio),and so these banks are using the Fed’s reverse repo facility to earn interest safely.

Now you may be thinking: this means much of the reverse repo money likely can’t be used to buy USTs either, then.

True.

Which is why the Treasury may be forced to issue a whole lot more shorter-dated paper, i.e., T-Bills, instead of longer-dated Treasuries. This way, the cash that is currently parked in the reverse repo facility can be used to fund the Treasury’s needs.

Because T-Bills fall outside the SLR calculations.

And so, if the Treasury does not want to issue shorter paper, then it will have to work with the Fed and regulators to have the SLR ratio limits raised so banks can own more longer dated Treasuries.

Bottom line, if the $1T of Treasuries soak up reverse repo cash, it is not a form of QT, as this money is otherwise idle. It is not a tightening measure, IMO.

And so, if the Treasury leans this way and finds a mechanism to draw from reverse repo instead of reserves, then the impact of borrowing another $1T can be partially or mostly muted.

Otherwise, there will be a tightening effect on the economy.

OK, now for a little update here since I wrote this, let’s look at how the Treasury is doing and how the market is absorbing it thus far.

As expected, the Treasury has been issuing mostly short paper—or T-bills—floating $590 billion in short paper so far in June. They’ve also issued $120 billion in notes which mature in 10 years or less. And they have auctions scheduled for another $300 billion of paper—half are short term T-Bills again, and half are 2 to 7yr notes—in the next week or so.

Add that all up and it looks like we were right on the money in our estimates of $1 trillion of Treasury needs this month.

So where has it been soaked up, so far ?

Well, a large portion of the $225 billion of maturing debt has presumably been rolled from maturity right back into USTs

Bank reserves have net dropped by $50 billion this month, so some have been soaked up there.

And the Reverse Repo facility has fallen by $260 billion.

That all adds up to $535 billion, leaving about 55B for foreign investors.

Well done, Treasury, tapping that parked reverse repo cash.

But there’s still a small problem.

Virtually all of that $590 billion of T-Bills floated matures in just a few weeks or months, and so the Treasury will have to just roll it again…and again…and again.

Bad news: the yields are much higher for short term paper than longer term.

Good news: this keeps the Treasury from being locked into long-term high rates, which will negatively impact the deficit for longer. When rates do come down (and they will in the next year or so, in my opinion), the Treasury will be issuing at lower rates again.

But they will still have a structural issue of swapping reverse repo for T-Bills. And so, unless the Fed stops QT and ultimately steps back into the market to monetize the debt again, the Treasury will have to keep playing this game of reverse repo to T-Bill musical chairs.

Allowing the deficits to continue to bloom, and the debt to continue to spiral higher.

So, where does this all leave us as investors?

In short, I’m waiting to see whether the Treasury puts stress on the bond market by trying to sneak in longer dated paper. And whether they start to impact liquidity and threaten to lock up the markets (i.e, break things). This could very well lead to a major credit event.

As such, I’m watching Treasury auctions closely.

And how do the auctions themselves go? Are there signs that the flood of USTs is putting stress on the bond market, in particular? Or does the market remain largely healthy?

Also, do they try to adjust any rules or the SLR calculations? Or the bank reserve rules and requirements, allowing andrequiring banks to hold more Treasuries.

Amid all this, I am also watching for signs that we are slipping into a recession, which could happen rather quickly, as the Fed has raised rates so dramatically.

Because in reality, the true economic impact of all that Fed tightening, and now more at the hands of the Treasury, have largely yet to be seen.

So, as we used to say in hockey: keep your head on a swivel and be ready for anything.

Pod: The Great Treasury Re-Funding